Dwellings inhabited by enslaved people were crowded, crudely built, and scantily furnished. These original, 170-year-old dwellings inhabited by enslaved people tell an important story about enslavement in America and its legacy. — Bryan G. Stevenson

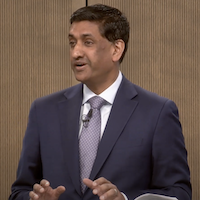

On March 27, the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park officially opened in Montgomery, Alabama — the newest extraordinary Legacy Site created by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). EJI is a nonprofit human rights organization committed to ending mass incarceration and excessive punishment in the United States, challenging racial and economic injustice, and protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society, all under the leadership of visionary Founder and Executive Director Bryan Stevenson.

The Legacy Sites are three spaces in downtown Montgomery that help tell the story of our nation’s legacy of racial violence and terror and our ongoing struggle for equality and justice. The Legacy Museum sits on the former site of a cotton warehouse where enslaved people once worked, and uses interactive exhibits, video and digital pieces, and the work of dozens of contemporary artists to take visitors on a moving journey from the transatlantic slave trade to contemporary America. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is a monument and sacred space that honors the more than 4,400 black people who were killed in racial terror lynchings in our nation between 1877 and 1950, listing their names on more than 800 steel columns, one for each county where these murders took place. Now, the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park, which sits on 17 acres overlooking the Alabama River, brings EJI’s commitment to truth-telling to a new landscape.

EJI explains that the new site intends to put the history of slavery in context, with sections of the park dedicated to the transatlantic and domestic trades of enslaved people, the laws surrounding slavery, enslaved people’s labor, and their “escape, rebellion, and resistance to slavery. The narrative journey includes love, death, family, and faith.” The nearly 50 extraordinary sculptures set throughout the site do much of this storytelling. They include newly commissioned works and powerful large-scale pieces by Charles Gaines, Alison Saar, Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, Simone Leigh, Wangechi Mutu, Rose B. Simpson, Theaster Gates, Kehinde Wiley, Hank Willis Thomas, and many more.

The abduction, abuse, and enslavement of Africans trafficked by Europeans across the Atlantic Ocean altered the global landscape and created a legacy of suffering and bigotry — Bryan G. Stevenson

The art sits alongside historical references, including a rail car like the ones that carried enslaved passengers as cargo on the nearby tracks and a pair of 170-year-old cabins from Marengo County, Alabama, in which enslaved people lived. At the park’s core is the National Monument to Freedom, a 43-foot-tall, 155-foot-long structure shaped like an open book that includes the surnames of 122,000 Black families listed in the 1870 U.S. Census, the first census in which formerly enslaved African Americans were counted by name. The book’s “spine” features this engraving: Your children love you. The country you built must honor you. We acknowledge the tragedy of your enslavement. We commit to advancing freedom in your name.

In an interview about the Legacy Sites, Bryan Stevenson said: “I do think we’re at a moment where we’re debating whether we’re going to be honest about our history, about our past, and learn from it, reckon with it, and move forward, or we’re going to double down on silence and these false narratives. What I’m encouraged by is that we’ve had hundreds of thousands of people come since we opened the [first site] in 2018. And most of them say, ‘I didn’t know this.’ But not only have they come, they’ve left with a new understanding about what we have to do to make progress in this country. I don’t want to talk about slavery and lynching and segregation because I want to punish America. I want us to get to a better place.”

He went on: “I believe there’s something better waiting for us. There’s something that feels more like freedom in this country. There’s something that feels more like equality, feels more like justice. But we can’t get there if we continue believing these false ideas about our greatness, about our failures, that we never made any mistakes, we never did anything wrong. And I actually hope that this moment illustrates the importance of this conversation that we’re trying to have about a time for truth-telling.”

Many of us are the heirs to … extraordinary perseverance and hope.”

Now, as the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park welcomes it first visitors, Stevenson says: “I believe this will become a special place for millions of people who want to reckon with the history of slavery and honor the lives of people who endured tremendous hardship but still found ways to love in the midst of sorrow. Many of us are the heirs to that extraordinary perseverance and hope. There is a lot to learn at this site, and we want everyone to experience it.”

It was a terrible irony that the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park opened in the same week that the state of Alabama passed new legislation banning public schools and universities and state agencies from sponsoring diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, along with banning transgender students at public colleges and universities from using campus restrooms that match their gender identity. Yet that timing only underscored the profound importance of EJI’s Legacy Sites and their unwavering determination to honor and share the truth. All of us who are “the heirs to that extraordinary perseverance and hope” described by Bryan Stevenson are deeply grateful for this work.

• • •• • •

• • •• • •

Marian Wright Edelman is Founder and President Emerita of the Children's Defense Fund whose Leave No Child Behind® mission is to ensure every child a Healthy Start, a Head Start, a Fair Start, a Safe Start and a Moral Start in life and successful passage to adulthood with the help of caring families and communities.

Marian Wright Edelman is Founder and President Emerita of the Children's Defense Fund whose Leave No Child Behind® mission is to ensure every child a Healthy Start, a Head Start, a Fair Start, a Safe Start and a Moral Start in life and successful passage to adulthood with the help of caring families and communities.

Black History, Women's History: Ella Baker

Black History, Women's History: Ella Baker