Where have all the lawyers gone?

Musings on the Minor Bar Association Trailblazer Awards

Today the Norman S Minor Bar Association hosted its annual Trailblazers luncheon at a posh downtown hotel. Today's luncheon was a celebration of the wildly successful careers of three extraordinary African American attorneys: Randolph Baxter, Paul Harris, and Yvette McGee Brown.

Judge Baxter served with distinction for more than a quarter century as a US Bankruptcy Court Judge. Judge McGee Brown rose to the highest echelons of her profession when she was appointed to serve on the Ohio Supreme Court. And Paul Harris has over the years emerged as one of the most influential behind the scenes leaders in Cleveland's professional and civic circles as corporate counsel at KeyBank.

The resume of each of these lawyers is impeccable, and filled with community service beyond their outstanding legal accomplishments, a larger record of which can be found here. Indeed, while Judge Baxter has been retired for some years, Judge McGee Brown and Mr. Harris will no doubt continue to be active community leaders for some time, Harris here in Cleveland and McGee Brown in Columbus where she is now a partner in Jones Day, one of the world's leading law firms.

The Norman S. Minor Bar Association is itself to be saluted for continuing its unblemished record of highlighting the best and brightest careers that black lawyers are forging against the odds.

And make no mistake; even the law profession itself recognizes how daunting the prospects are for black attorneys to succeed. Just this year both the Cleveland and Ohio bar associations addressed rampant discrimination within their own ranks. Leadership within each of these organizations has stepped forward to address the ways in which America’s original sin continues to infect personnel decisions in law firms and corporate offices.

I was a guest at several sessions addressing these issues at this year's annual Ohio State Bar Association meeting in Cincinnati. Hundreds of attorneys from around the state were held at rapt attention for the sessions I attended. One featured the incomparable Nathaniel Jones, a retired federal appellate court judge of the Sixth District based in Cincinnati. Judge Jones deserves a post of his own and we will soon deliver on that responsibility, especially because a part of his remarkable journey left indelible tracks here in Cleveland.

The most lasting takeaway from the State Bar meeting was the presentation on implicit bias. Some may have recognized that phrase when Hillary Clinton used it this month in her presidential campaign while responding to a question about police practices. The oppositional heat her mere use of the phrase generated was irrefutable proof that implicit bias resides as a virulent force in the body politic.

My real concern here, enmeshed in today's worthy celebration of noteworthy careers, is how these successes seem in some ways increasingly estranged from the communities that made them possible.

Community has been a focus of ours these past few weeks. Much of this recent conversation has focused on Glenville — the warm, rich, diverse and vibrant neighborhood of my youth. What happened to it? Why did it happen? Most importantly, what can be done to renew it?

To the latter point, Glenville's community development corporation, the Famicos Foundation, held its second annual fundraiser last night, where it unveiled a master plan1 into which more than 500 of its estimated 20,000 residents had input. As we surveyed the nearly 200 supporters in attendance, we recognized several black attorneys of our acquaintance — Vanessa Whiting, Sheila Wright, Mona Scott, among them. While Ms. Whiting is in private practice, and a fierce and devoted warrior in the ongoing struggle for racial and social justice, we didn't see one attorney there who might routinely address the legal issues of ordinary community residents.2

The absence of black attorneys whose practices are rooted in the community is starkly emblematic of larger issues. Back in the 1950s and early 1960s, when America was great (chuckle, chuckle) black attorneys in high-powered corporate legal circles were more rare than hen's teeth. But there was an abundance of black lawyers in the community, with offices in plain sight up and down Cedar Ave., East 55th, and East 105th. Former Congressman Louis Stokes noted in his just-published posthumous memoir how proud he was to open Stokes and Stokes with brother Carl on St. Clair Ave., immediately east of East 105 St. Ironically, that office was short-lived: not long after it opened, Lou's jaw dropped when the already-legendary Norman S. Minor himself stopped in unannounced to invite the brothers to join him in establishing Minor, Stokes and Stokes.

The record shows there never have been more talented lawyers of any hue than the community-based Norman Minor and Lou Stokes. As opportunities slowly began to open in the legal profession in the late Sixties, black attorneys, including black women attorneys, began to show their extraordinary professional competence on a wider stage, even while regularly battling outright hostility — to say nothing of implicit bias — from colleagues, judges, and corporate clients. The experiences of early pioneers like Paul White (Cleveland’s first black law director and subsequent Baker Hostetler partner) Owen Heggs (Jones Day), Andrew L. Johnson, (first black president of the then-4,000+ member Cleveland Bar Association), or Leonard Young (Ferro Corporation) were fraught with aggressions both macro and micro directed their way.

We have come a mighty long way. Today, we are no longer surprised to learn that Robyn Minter Smyers has been selected to lead Thompson Hine, that Rhonda Ferguson is chief legal officer at Union Pacific, or that the aforementioned Paul Harris is KeyCorp general counsel. We have no doubt they earned their positions and the perks attached thereto. Undoubtedly they heeded the injunctions of the ancestors to be twice as good.

But something has also undoubtedly been lost when black neighborhoods are no longer home to the legal descendants of Norman Minor, Lou Stokes, Perry B. Jackson, Jean Murrell Capers, Lillian W. Burke, John W. Kellogg, Al Pottinger, Stanley Tolliver, and a host of others. Glenville councilman Kevin Conwell touched on this last night when he talked about the paucity of day-to-day role models in the community.

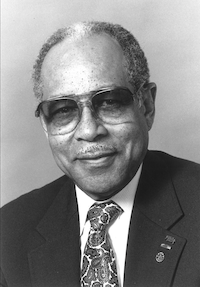

Marvin M. Fisk, D.D.S.

The absence extends to professionals of all stripes. Commercial thoroughfares in black communities were once full of physicians, accountants, and dentists. I remember the much-beloved Marvin Fisk actually living above his dental office at 8923 Cedar Ave. Dr. Fisk served his profession and community well enough to be recognized with an annual award given by the Ohio Dental Association.

I'm not a Luddite. I don't wish a return to the glorious days of somebody else's mid-century America. I don't even pine for the glorious days of the Kansas City Monarchs and the Cleveland Grays of the old Negro Leagues, though I would love to have seen Satchel Paige on the mound, Josh Gibson at or behind the plate, and most especially Cool Papa Bell on the base path.

Nonetheless, something has clearly been lost. The path to desegregation, integration and inclusion has parallel tracks labeled corporatization and monetization and globalization that have collectively assaulted our Glenvilles, Houghs, Centrals, Fairfaxes, Mt. Pleasants and Lee-Harvards. Independent doctors have all but disappeared; virtually all are now on the payroll of our local medical behemoths. Solo legal practitioners operate from home or have flexible virtual space in suburban office parks. Dentists may retain the best balance in terms of independence, community connections, and compensation.

Mike Nelson, current president of the Cleveland NAACP is perhaps the last African American to have run for significant non-judicial political office from a private law practice base. Almost all black judicial candidates run from the cover of a job. Common Pleas Court Judge Cassandra Collier-Williams was a notable, and successful, exception. Is the quality of our political representation diminished by the reluctance of our highly trained legal talent to get into politics?

We only intimate here the challenges ordinary central city residents face in securing affordable professional services to help navigate their lives. Transportation can become a major obstacle when you can no longer walk or take a simple bus ride to a lawyer, doctor, accountant, dentist or realist’s office.3

How do we bridge the aching chasm between our professionals and the ordinary Willies and Willie Maes whose protests and votes and marches and demonstrations and riots helped open the doors so that our prodigious natural talent could attain a broader platform?

What are your thoughts and observations?

I invite you to share your responses, ideas, and comments here. Those of you who do respond — I appreciate each and every response — typically do so by direct emails that we think have so far escaped Politburo attention. And I always reply. But these issues require a robust public discussion that we hope you will join.

• • •• • •

[1] The plan can be accessed here.

[2] John Anoliefo, executive director of Famicos, did announce his agency's free legal clinic and its valuable work in helping people caught up in our system of justice to get a solitary blemish expunged. More than 600 people have benefited from this service, which I think he said is open to all. Call 216.791.6476 for more information.

[3] The term Realtist may seem a typo to some. It relates to the fact that black real estate agents were excluded from membership in the all white realtors association and even un able to access the comprehensive listing service of properties available for sale, just another way segregation and subjugation were reinforced. The Realtors went so far as to copyright the word Realtors, forcing black agents to invent a new term — Realtist — for their organization.

Originally published October 23, 2016 on The Real Deal Press companion site. Updated May 17, 2021.