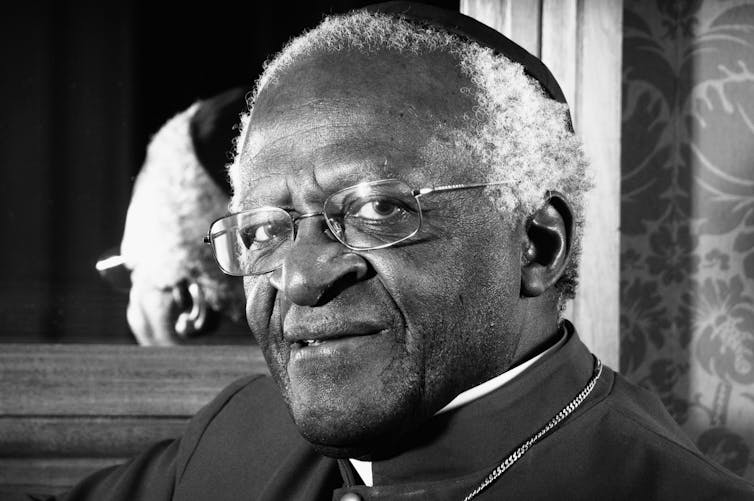

With the recent deaths in 2021 of South African Anglican Bishop Desmond Tutu on Dec. 26 and Frederik Willem (F.W.) de Klerk on Nov. 11, three of the men that laid the foundation to transform South African society are no longer able to see the result of their work – and the growing disillusionment over the lack of progress.

The deaths of Tutu and de Klerk evoked the dark days after Nelson Mandela died in 2013, when hundreds of thousands of South Africans traveled from across the country, spending hours and sometimes days in long queues to pay their final respects.

As a 32-year-old, native South African, I once believed that giants like Mandela and Tutu – de Klerk’s role was always questionable – had entrusted us with a new South Africa. As a legal theorist, I now see instead that they left us merely with an invitation to make that dream into reality.

Their lasting legacy is a deep and abiding commitment to the rule of law that belongs to all South Africans equally. I wonder how long that legacy can survive alongside extreme inequality.

Past Injustices

Back in the early 1980s, a grassroots movement took hold throughout the United States. It was part of an international effort, energized by unrest on college campuses, to end one of the most racist regimes in modern-day history.

Much like the United States, South Africa was shaped by more than three centuries of colonialism, slavery, violent racial conflicts and racial segregation. Started in 1948 and known as apartheid, the violent system of legal segregation finally ended in the early ‘90s in part because of the anti-Apartheid movement in the United States and across the world. The system was brutal, and it was enforced with all the coercive machinery of the state, including government-sanctioned death squads that tortured and killed scores of anti-apartheid activists.

we remember the past so that we can imagine alternative futures. — South African historian Jacob Dlamini

Among those killed was Stephen Biko. The founder of the Black Consciousness Movement, Biko was found dead after being tortured while in police custody. His murder in 1977 sparked an international outcry.

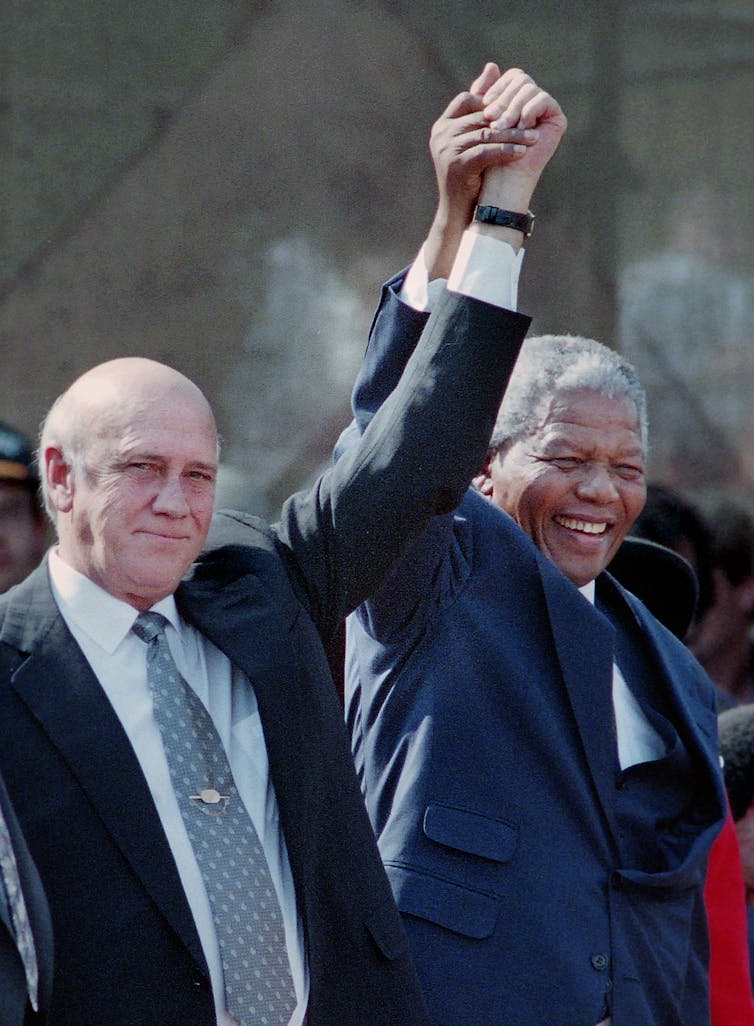

The moment of racial reckoning hit its zenith in 1990 when the South African government released Mandela, the leader of the African National Congress, from prison after serving 27 years. Convicted of acts of sabotage against the South African government, Mandela was punished for his unrelenting efforts to gain full citizenship rights for nonwhite South Africans then ruled over by the white minority.

But apartheid’s prominent place in racial justice history is not only because of its status as a crime against humanity, but also how it came to an end. Apartheid wasn’t eliminated after a widely predicted violent civil war, but rather in a legally negotiated, largely peaceful, constitutional transition. Ultimately, the dismantling of apartheid came by the hands of South Africans.

With the transition came international acclaim and three Nobel Peace Prizes. The first was awarded in 1984 to the Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, Tutu, “for his role as a unifying leader figure in the non-violent campaign to resolve the problem of apartheid in South Africa.”

The other two went to Mandela and de Klerk, the last president under apartheid, both in 1993, “for their work for the peaceful termination of the apartheid regime, and for laying the foundations for a new democratic South Africa.”

Unlike Mandela and Tutu, de Klerk remains a divisive figure. Indeed, both Mandela and Tutu were critical of him. During negotiations to end apartheid, de Klerk infamously told one of his cabinet members that “We are basically the liquidators of this firm.” It wasn’t until 2020 and while he was on his death bed that de Klerk unequivocally renounced apartheid – for the first time.

Reckoning

Tutu and Mandela recognized the need to deal – explicitly and purposefully – with the injustices of the past. To that end, the transitional South African Constitution included a section of “National Unity and Reconciliation.” The final constitution, one of the most progressive in the world, explicitly states that South Africans “recognize the injustices of the past” and commit the government to “establish a society based on democratic values, social justice and fundamental human rights.”

The South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, known as the TRC, represented a concerted institutional effort at such healing. It was established by legislation in 1995 to “establish the truth in relation to past events … in order to prevent repetition of such acts in the future.”

Over the course of four years of public hearings, perpetrators came forward and confessed, victims told their stories and reports were made public.

Acknowledging the past has its merits. Legal scholars such as New York University Law Professor Peggy Cooper Davis suggests that the United States is in need of a similar process of collectively facing the truth in its own reconciliation about “group-based cruelties.”

But in the end, South African reconciliation was never merely about burying the past, it was about building a future. As South African historian Jacob Dlamini has argued in his book, “Native Nostalgia”, we remember the past so that we can imagine alternative futures.

That future remains elusive.

Present inequality

The wealth gap in South Africa is one of the highest in the world and remains largely unchanged since the end of apartheid.

For most Black South Africans, the reality of life remains on the margins of an economy set up to serve a class of privileged few. White unemployment is around 9%, black unemployment is 36.5%. Income in the country remains “heavily racialized”: White South Africans earn, on average, three times more than black South Africans.

An uncertain future

Widespread student protests in 2015 have been characterized by some as the first sign of a profound disillusionment with the new South Africa. Similar disillusionment was visible in widespread riots in 2021.

It is in this crucial moment of disillusionment that South Africans are left to fend on their own without the leadership of our founding fathers.

They did not, we see now, leave behind a transformed South Africa.

As Tutu said in his foreword to the TRC report in 1998: “The past, it has been said, is another country. The way its stories are told and the way they are heard change as the years go by. The spotlight gyrates, exposing old lies and illuminating new truths.”

He then explained: “The future, too, is another country. And we can do no more than lay at its feet the small wisdoms we have been able to garner out of our present experience.”

Tutu’s lesson to South Africans was that by accounting for the past, we are also becoming accountable to the future. Ultimately, reconciliation lies in the much harder work of committing to a just future – a task that remains unfinished.

• • •• • •

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Alma Diamond is a Candidate, Doctor of Juridical Science, New York University