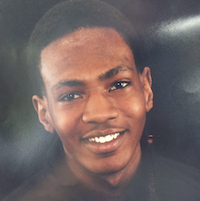

When we learned of the death of Jayland Walker in our hometown community of Akron, our hearts were broken again. In other words, we added his name to the list of young Black men and women we are still grieving. As ministers, as Grief Recovery Method specialists, and as members of this community, we know grief is the normal response to losing those we have loved. And we know that losing a loved one hurts.

What we don’t speak of enough, however, is the accumulation of grief that happens with one loss after another, with one tragedy after another, with one injustice after another. That accumulation of grief does not only affect us individually, but it affects us collectively, as a people, as a community. The question is when was the first time, if this feels like the umpteenth time, a number we use in the Black community to signify that we are sick and tired of counting? When we know our history, we know the first time is too far back — 1619 — or we know counting all the deaths, the inequities and the examples of injustice would make us weep, so we pause to bear witness to the love, the loss, and the need to lament in times like these, nevertheless.

What is lament? Why do we need to make space for it as a spiritual practice? Lament is verbalized grief. It is the practice of giving words and maybe even a cry out to God for the sorrow and loss we cannot bear alone. We know the disproportionate toll the pandemic of COVID-19 has had in our community. We know the health disparities that ravaged our community even before the pandemic. We know the ways in which the educational system throughout our nation’s history has not done right by our children. And we bear witness to the aftermath of redlining and unequal opportunity that has locked many families of color in cycles of poverty in neighborhoods where they are disregarded.

Of course, we know we are a resilient people. We know we are people of faith and people of prayer who care not just about ourselves but one another. But we know that our love for our community — coupled with the assaults on our individual and collective hearts, bodies, and minds — also means we experience the normal manifestations of grief including anger, sadness, and deep sorrow. We experience it collectively as people who know and embody our history, every time we walk out of our homes, go to the grocery store, school, the bank, or our places of worship. We feel the woundedness and hurt of being treated as if our lives do not matter and the loss cuts so deep that we move from grief to lament. We think of Willy Loman’s wife in Death of a Salesman when she cries out “attention must be paid,” and that feeling begins to express our need for lament.

Lament is a cry out to God when systems fail us, when the very ones we thought would care, don’t, and when we are sick and tired of being sick and tired.

We stand in solidarity with the Walker family and other grieving families because we want them to know they are not alone in their grief for their loved ones, their cry for justice, and their plea for peace and non-violence.

So this is a time for lament because grief is cumulative and it is collective. Lament gives words to our sorrow, and it inspires us to fight for change. And we will not give up. We will not stop fighting for justice even as we cry out in pain for our wounded hearts. We express not only our individual grief, but our collective grief for recent losses and those that have accumulated over time.

We are tired. But as the song by Sweet Honey and the Rock says, we who believe in freedom shall not rest until it comes.

• • •• • •

Bishop Joey Johnson is founder and Preaching Pastor of The House of the Lord in Akron and a certified Grief Recovery Method specialist.

Marilyn S. Mobley, PhD, Associate Minister, Arlington Church of God in Akron and an advanced certified Grief Recovery Method specialist.