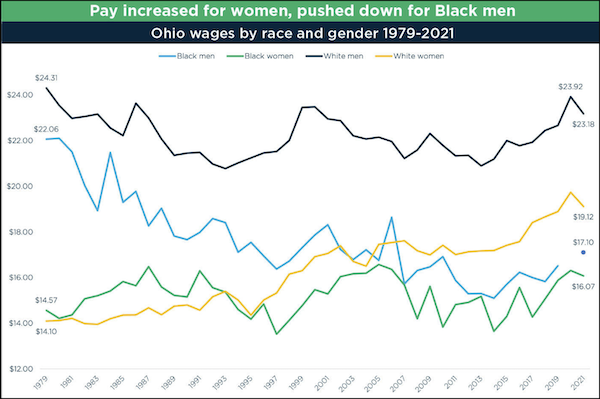

Everyone who works – regardless of their race - deserves a wage that honors the value of that work and meets the cost of living. Yet as working Ohioans have produced record wealth nearly every year for decades, rich corporations have rigged the rules to capture the gains for themselves. As a result, working people’s productivity is not reflected in their paychecks. Employers have suppressed wages for nearly all working people since the 1970s, but the cost has not been borne evenly. While some workers secured meager pay growth, employers actually pushed pay down for others. Over the past four decades, the pay gap between black and white workers has become a cavernous gulf. Black men have borne the highest losses.

Employers successfully pushed black workers’ pay down by just under $1 per hour since 1979 — in many cases with policymakers’ help — over a time when white workers’ pay rose $1.73 per hour. Zooming in further, black Ohioans’ overall pay cut was borne entirely by black men. Black women’s pay actually rose by $1.50-per-hour — albeit far less than the $5.02 per hour for their white female counterparts. Yet wages for black men were pushed down nearly $5-an-hour, compared to a cut of $1.13 for white men.

What is going on here?

Some policy choices have hurt working Ohioans across the board and they’ve coupled with efforts to preserve racial advantages for white people. Others have specifically targeted black men. The result has been disastrous for many black men.

Ohio’s once strong wages, sustained by a growing manufacturing sector and robust union membership, made our state a destination for Americans seeking a better life, including the descendants of enslaved people who came during the Great Migration. But beginning in the 1970s, tax and trade policies encouraged corporations to seek the cheapest labor they could find on the globe, regardless of working conditions. Excessive interest rates engineered by the Federal Reserve to curb inflation in the 1980s exacerbated the problem: a corollary to rapid rate hikes the Fed is now pursuing today. And sustained corporate attacks on unions decreased the share of Ohioans who belonged to a union by two-thirds.

The past 40 years has been hard for many working Ohioans, but black people face a growing wage gap and are twice as likely to be unemployed as their white counterparts.

This is not an accident.

Black people face a growing wage gap and are twice as likely to be unemployed as their white counterparts.

This is not an accident.

Economist Erin Wolcott has found that some policymakers, acting to protect race and class advantages and maintain de facto segregation, reversed many of the labor protections established by and following the New Deal, after the 1964 Civil Rights Act included black Americans in those protections. Since then, policymakers let inflation push down the federal minimum wage, which would be worth nearly $14-per-hour today. They reduced unemployment benefits, leaving 750,000 working Ohioans ineligible if they were to lose their jobs tomorrow, mostly due to low pay. And they supported policies that helped corporations crush unions or avoid union drives. These actions mirrored moves to close public parks, pools and even schools in effort to avoid integration.

This anti-black racism set America apart from other developed western democracies which went through similar technological change and similarly opened their borders to increased trade. Wolcott found that such policies account for 60% of the pay gap between the highest and lowest paid workers. Efforts to keep black people from enjoying full participation in the American economy have gutted the middle class and harmed working people of all races.

But they have harmed black workers more.

more than 850 laws and administrative rules limiting work opportunities for Ohioans with a criminal record serve to collectively import racism from the criminal legal system into the labor market.

Other factors are highly specific. Black men were targeted by “tough on crime” laws during the failed war on drugs. The criminal legal system that treats black men more punitively at every stage of interaction, from whether police are called to the severity of the sentence if the person is convicted of a crime. Ohio’s prison population quadrupled in the four decades beginning in 1978 to nearly 44,000 inmates today. By July 2022, about 6% of Ohioans were black men, but they comprised 43% of the state’s prison population. And more than 850 laws and administrative rules limiting work opportunities for Ohioans with a criminal record serve to collectively import racism from the criminal legal system into the labor market.

Black women of course faced the same racism their male counterparts did. The fact that black women were able to navigate the hurdles to secure higher pay over time is likely the result of pursuing more diverse and better-paying career paths than were open to their mothers and grandmothers: in 1935, half of African Americans were employed in domestic and agricultural work. Labor force data also show that black women have always worked, for many years at higher rates than their white counterparts: their higher pay than white women as recently as the early 1990s likely reflects having been more connected to work, while white women — at least those in middle income families — had more ability to take time away from work for other activities including child caregiving. While these factors have helped black women to secure higher pay than their counterparts four decades ago, they are still paid far less than they should be.

Low pay for black Ohioans is a clear sign of policy failure, but perhaps the most surprising thing about these trends is that we have done better in the past. After landmark civil rights wins in the courts and legislature, other factors have pushed down black Ohioans’ pay and made their connection to the middle class more precarious. These factors flow from policies that allowed corporations to consolidate power over working people, given them record profits during a global pandemic, and then allowed them to drive up prices. These are just the capstone on 40 years of corporations grabbing the gains while working Ohioans — black, white, and brown — produced more wealth for our state than ever before in history. We all have a stake in reversing that power imbalance, giving workers a voice on the job, and ensuring that everyone in Ohio is paid a fair wage that dignifies the value of their work.

• • •• • •

Michael Shields is a Researcher with Policy Matters Ohio.