On the day of the Super Bowl, Matt Gaetz, a Republican member of Congress from Florida, publicly announced that he would not watch one of the most popular sporting events in America.

The reason for his boycott?

“They’re desecrating America’s national anthem by playing something called the ‘black national anthem,’” Gaetz explained.

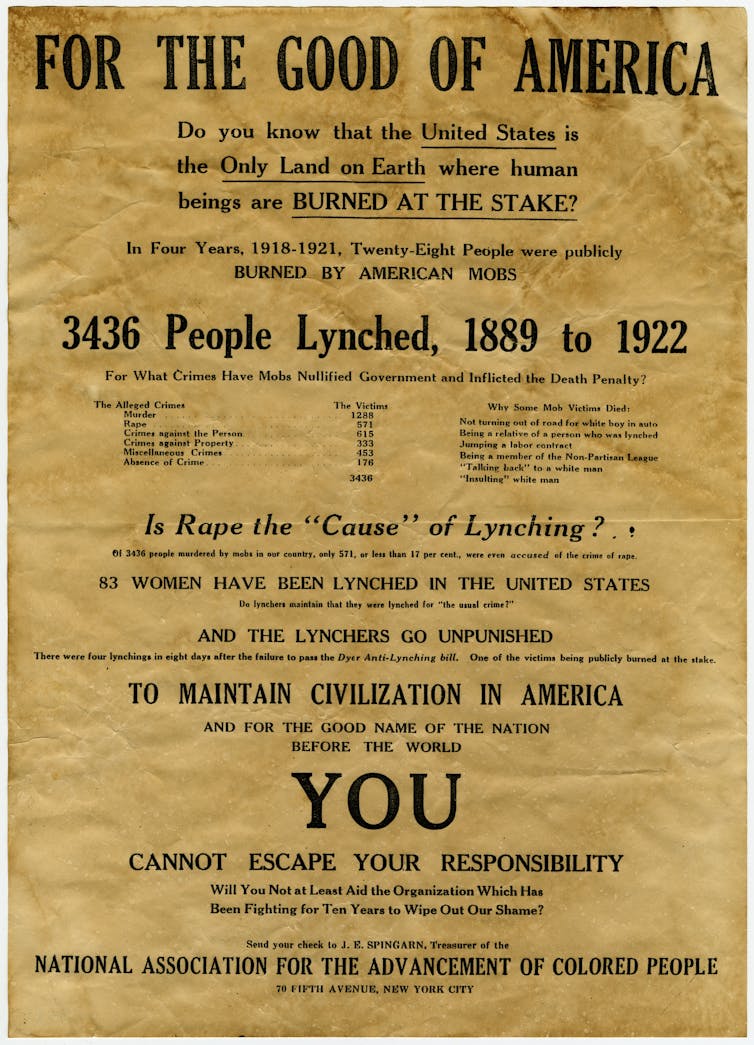

The song he criticized is “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” which was written by James Weldon Johnson and his brother Rosamond Johnson in 1903. For more than a century, this hymn has celebrated the faith, persistence and hope of black Americans.

“Lift Every Voice and Sing” was sung at the Super Bowl by Andra Day, after Reba McEntire sang the national anthem.

Whether or not Gaetz’s racist antic was the result of ignorance about the song’s legacy, it is clear that there is a knowledge gap between black and white students on our nation’s racial history. This gap makes it vital to teach high school and college students more African American history, not less, as Republicans have mandated in many states, including Gaetz’s home state of Florida.

As someone who teaches black history to mostly white college students, I have seen how learning this subject can create the understanding and empathy needed to bridge America’s racial and political divides.

Despite what Republican politicians have claimed, learning black history does not generate guilt or shame among students.

Who was James Weldon Johnson?

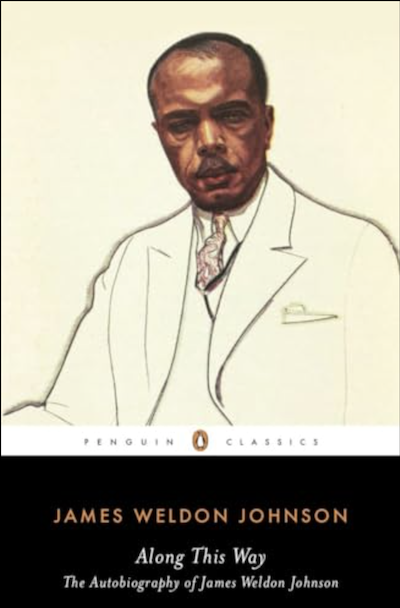

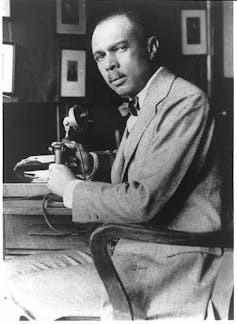

In my Black American Narratives class, we are currently reading James Weldon Johnson’s 1933 autobiography “Along This Way.” Johnson’s life provides a rare example of the opportunities that existed for very few black Americans after the Civil War and before white Southerners wrested away those possibilities through the creation of Jim Crow laws and social customs that maintained white supremacy.

Johnson’s parents grew up free – his father in New York and his mother in the Bahamas. Both were literate at a time when 80% of black Americans were not. These advantages helped them become homeowners when many Southern black families lacked the money to buy land.

Raised with this rare opportunity, Johnson thrived.

He graduated from Atlanta University in 1894 during an era when only about 2% of 18-to-24-year-olds in the U.S. received any college education. He became a high school principal in his native city of Jacksonville, Florida, the editor of a daily newspaper and the first black Floridian to pass the state bar exam.

He published poetry and novels, produced musical theater and served as U.S. consul to Venezuela. He was a professor at New York University and Fisk University and the first black executive secretary of the NAACP. While Johnson’s successes were extraordinary, they illuminate what black Americans could achieve when provided with even the narrowest avenues for advancement.

The accomplishments of Johnson and contemporaries such as Moses Fleetwood Walker, Ida B. Wells and George Washington Carver help students today understand that black Americans’ struggles were predominantly the product of barriers created by white supremacists rather than their own shortcomings.

The knowledge gap

Normally, I play “Lift Every Voice and Sing” for the students when we reach the part of Johnson’s autobiography that covers his writing of the song, but the immediate relevance of Andra Day’s version justified playing it a few classes earlier this semester.

When I asked who knew the song, both black students in my class said they did, but only two of the 24 white students raised their hands. That gap has remained fairly consistent during the four years I have taught Johnson’s autobiography.

We discussed the importance of the song, then turned to that day’s assignment.

In his book, Johnson discusses his experience as a summer school teacher in rural Georgia during the 1890s. He described those months as his “first tryout with social forces” and “the beginning of my knowledge of my own people as a ‘race.’”

We reviewed his first encounters with “White” and “Colored” signs on bathroom doors, and the laws and unspoken traditions of segregation that this young man learned during his time in the rural South.

Students often regard these “social forces” as ancient history, so I explained that these same traditions caused the murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955 after he spoke to a white woman while buying candy in a Mississippi store. They were startled to hear Till was born the same year as my father, making him about the same age as many of their grandparents.

Then I mentioned that even in 2012, Trayvon Martin was killed for walking through a predominantly white neighborhood at night while wearing a hoodie.

Silence.

“How many of you know about Trayvon Martin?”

The two black students raised their hands. The white students looked at me blankly.

Stunned, I told them the story of Martin’s death, but in the moment I couldn’t remember his killer’s name.

One of the black students quietly said “Zimmerman.”

These students were only 6 or 7 when Martin died, so not remembering the event is understandable. Not learning about it since then highlights the continuing racial divide in our children’s education.

When students do learn this history, it can literally improve the culture of a campus and a city.

Students from these classes have helped to strengthen the relationship between the Black Student Union and the Jewish student organization Hillel on our campus. They have also conducted interviews with alumni of the local high school who attended classes during the racially segregated days of Jim Crow.

In another example of gaining firsthand knowledge, students have attended Sunday services at a local historically black church – a first experience for most of them. These students subsequently helped the congregation build a mobile exhibit about the church’s history.

Despite what Republican politicians have claimed, learning this history does not generate guilt or shame among students. It often inspires them how to reach across cultural divides in ways they have never attempted before.

The value of Black History

Most students enter my class knowing only of Rev. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, Rosa Parks’ bus protests or Malcolm X’s activism. Some may know about Jim Crow.

But white students tend to know little about the recent history of racial violence in the U.S. They are familiar with George Floyd and the protests that emerged after his murder by a white police officer, but few other recent victims of this kind of violence.

Ferguson, Missouri, where protests led by Black Lives Matter emerged after 18-year-old Michael Brown was shot and killed by a white police officer, means little to them.

The problem is not a general lack of historical knowledge but its disparity along racial lines. Black students do know this history, or at least more of it than their white peers.

Teaching [white students] black history often inspires them how to reach across cultural divides in ways they have never attempted before.

Bridging this knowledge gap is made more difficult because today’s young Americans of different races do not sit in the same classrooms as a result of segregated schools in segregated communities – nor do they learn the same history.

Its my belief that schools fail all students when they omit the difficult parts of U.S. history. Teaching black history can create understanding and spark rare discussions on challenging topics across racial lines.

Those of us who actually teach these subjects recognize these benefits – no matter what the politicians say.

• • •• • •

Paul Ringel is Professor of U.S. History, High Point University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.