Earlier this year, in praise of President Joe Biden’s legislative agenda, some people suggested that he was like the second coming of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Congressman James Clyburn demurred. He said that Biden should not be like FDR. Perhaps he should be more like President Truman.

Many people were surprised at Clyburn’s statement. After all, was not FDR the reason African Americans switched from the Republican to the Democratic Party?

FDR’s relief programs during the Depression made him popular with many African Americans. Nevertheless, he did not aggressively promote civil rights or an anti-lynching law for fear of alienating Southern whites.

Key New Deal programs were discriminatory. The Social Security and the National Labor Relations Acts of 1935 excluded agricultural and domestic workers, effectively excluding African Americans, a large proportion of these workers. He did this in deference to Southern legislators in Congress.

Some historians have proposed that Southern employers worried that benefits in these programs would discourage black workers from taking low-paying jobs in their fields, factories, and kitchens.

In the 1930s, civil rights leaders were pushing FDR to support anti-lynching legislation. Walter White, executive secretary of the NAACP, requested a meeting with the President. Eleanor Roosevelt, who was very supportive of civil rights, arranged a meeting with her and FDR. At this meeting, FDR told Eleanor and White that he privately supported the bill but would do nothing to stop the Senate filibuster. He said he could not challenge the Southern Democratic leadership in Congress, an action that would risk his New Deal programs.

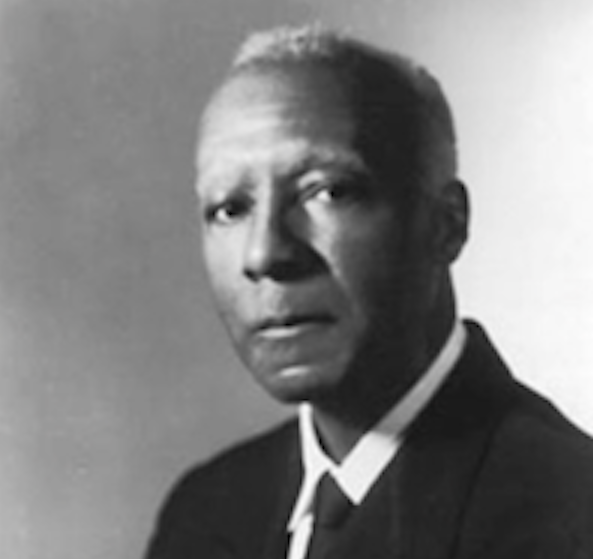

One of the most influential civil rights leaders of the 1930s and 1940s was A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, an all-black union of passenger train workers. Randolph became outraged over the practice of new defense plants refusing to hire qualified African Americans over less qualified white workers.

Randolph announced plans to march on Washington to protest this injustice. FDR’s response was a promise to quietly increase the number of African Americans in defense plants, which did not satisfy Randolph.

After meetings between Randolph and his allies and emissaries of FDR failed to solve the issue, FDR agreed to meet with Randolph, who asked the President to issue an executive order banning discrimination in the defense industries. When FDR demurred unless the march was canceled, Randolph said there would be 100,000 people coming. Please note that marches on Washington had not been peaceful like the later 1963 March on Washington. Consequently, officials were concerned about the effects of the protest.

One week after Randolph met with Roosevelt, the President signed Executive Order 8802 on June 25, 1941. It prohibited ethnic or racial discrimination in the nation’s defense industry. It also set up the Fair Employment Practices Committee.

President Harry Truman was more engaged than FDR on civil rights issues. In a message to Congress in February 1948, Truman asked for federal civil rights legislation, including anti-lynching laws.

In March 1948, Truman met with civil rights leaders to discuss segregation. Randolph told the President, “The mood among Negroes of this country is that they will never bear arms again until all forms of bias and discrimination are abolished.”

In June 1948, Randolph informed President Truman that if he did not issue an executive order ending segregation in the armed forces, African Americans would resist the draft.

A month later, with the election coming in four months, Truman signed Executive Order 9981, effectively integrating the armed forces.

Truman’s role in civil rights was a profile in courage, which we could not say about FDR.

• • •• • •

Wornie Reed is Professor of Sociology and Africana Studies and Director of the Race and Social Policy Research Center at Virginia Tech University. Previously he developed and directed the Urban Child Research Center in the Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs at Cleveland State University (1991-2001), where he was also Professor of Sociology and Urban Studies (1991-2004). He was Adjunct Professor at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine (2003-4). Professor Reed served a three-year term (1990-92) as President of the National Congress of Black Faculty, and he is past president of the National Association of Black Sociologists (2000-01).

This column first appeared online at What the Data Say and is shared here by permission.