CPL Writers and Readers program proves great way to wrap Black History Month

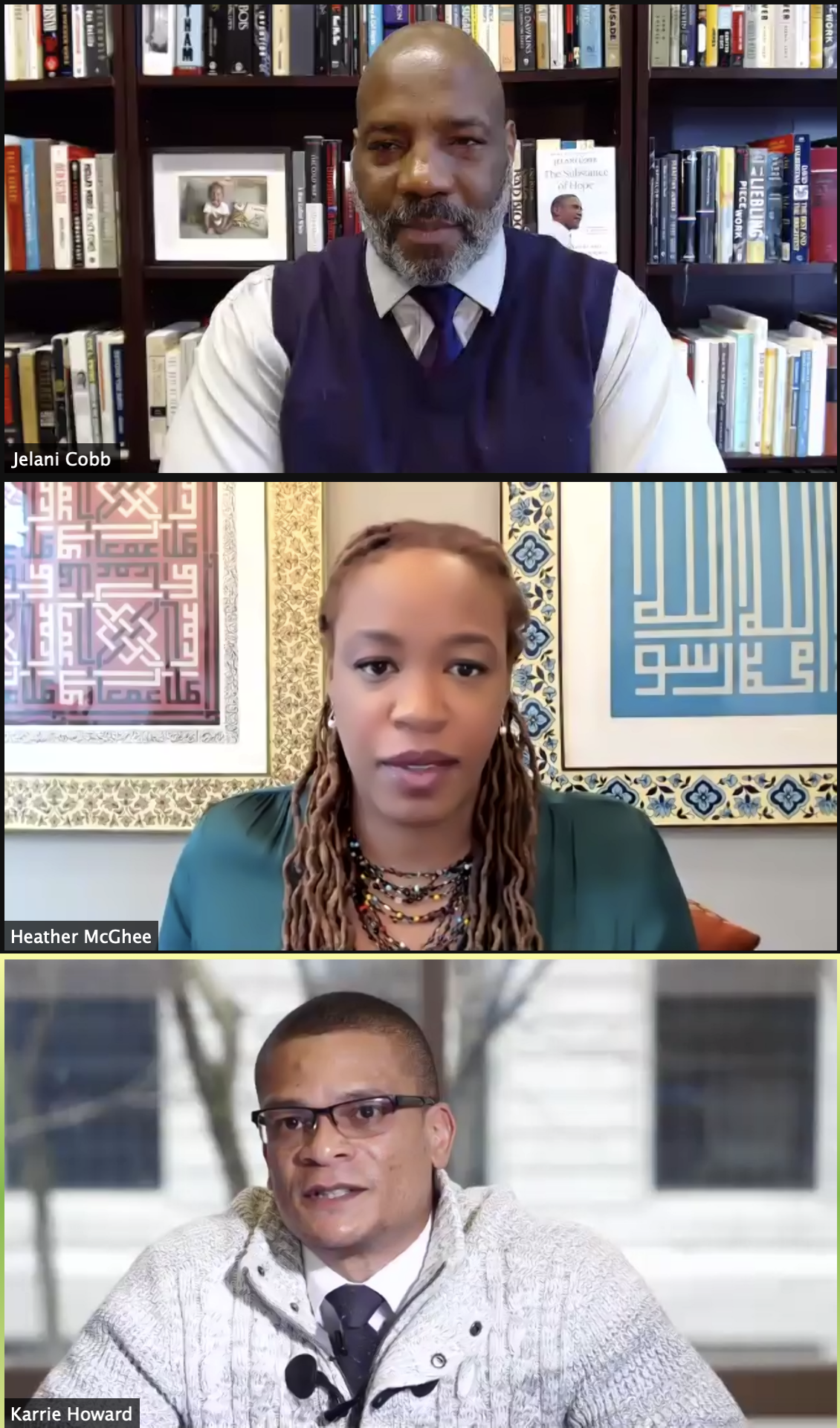

Let’s start with what went wrong Saturday at the Cleveland Public Library’s outstanding virtual presentation by writers Jelani Cobb and Heather McGhee, part of CPL’s recurring Writers and Readers series.

It wasn’t recorded. This omission was compounded by my tardiness in arriving. I mention this in the interest of transparency and to let readers know that my note-taking was less precise than normal as I scrambled to get down the uncommon wisdom that Cobb and McGhee were laying down.

Other than that, the program was rich in content, enlightening, informative, and even entertaining.

The noontime event was billed as a “candid conversation on policing in the 21st Century, but the discussion ranged far beyond that important subject. The breadth of the discussion was not surprising given both the erudition of the scholars and how many politicians and the public implicitly colorize the issue. To the likely surprise of some, Cobb responded to a question about “defunding the police” by saying the solution to police misconduct might require more funding rather than less. He suggested a lot more resources needed to be put into screening and training police recruits. “We train cops on the cheap,” he said, contrasting the way police often get minimal training before receiving license to kill, in contrast to several European nations where peace officer training can extend to more than a year.

McGhee picked up on Cobb’s point by noting that police training needed to result in ending the warrior mentality that exists within many police departments. She supports a reallocation of public safety budgets that tracks typical police and citizen interaction between as reflected most basically by police blotters. This would likely shift some public safety dollars toward problems of drug addiction.

Notwithstanding the stated focus on policing, the discussion ranged far and wide to include the so-called “education gap”, public policies and attitudes, and the allocation of public expenditures.

Cobb at one point segued to external threats to the U.S. He said that a bigger threat to the US than [somebody’s nuclear missiles] are the countries where people have more math majors than us.” He lamented the absurdity of the country’s racist attitudes in the intentional creation of the education gap. He said the US, especially in the South, did not want black people educated to maintain advantage for white people. This was tragic for all concerned as the costs of maintaining a dual society produced an inferior education system for white people and an absolutely atrocious one for black children.

The American thought process changed as other societies began to catch up with us with a novel emphasis on training all their people. We have yet to figure an effective way to dismantle our dual system and rectify its effects.

McGhee placed the underpinnings of this issue and many others on the belief that has been drilled into many white people that the public welfare is a zero sum game. Any resources going to another group reduces the public pie whose size is frozen. She illustrated how this narrow and outmoded thinking damages white people as much as it does black folk.

McGhee illustrated the problem by referring to how many communities responded to court orders to integrate their public facilities in the 1950s and ‘60s. Rather than desegregate, local government authorities often chose to drain public pools, i.e., to eliminate public amenities, thereby denying them to all citizens and thereby constricting the quality of public life for all.

As public facilities and programs came increasingly to be associated with minorities, especially black people, these government services were increasingly stigmatized and disparaged in a distinct reversal from the nation’s traditions.

When I logged in, McGhee was talking about how there has been a redefinition of “public” spaces over the years, a point she elaborates in her acclaimed new book, The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together. Public facilities and programs like public pools and parks and public housing are now disparaged because of their association with minorities.

McGhee summarized much existing scientific research when she spoke in generalities to point out that when white people are made aware of the country’s changing demographics — i.e., America’s browning — the effect is to make them more conservative. But she bashed the notion of a zero-sum game where gains by one group can only come at the expense of another. We have more in America than ever before, she said, so there is no need for folk to be afraid of scarcity.

Cobb observed that the zero sum game world view is not that of black people. He pointed out that during Reconstruction, when former slaves became legislators and public officials, their impulse was not to punish their former masters but to push for systemwide benefits like public education that lifted the entire society.

McGhee and Cobb concurred that public benefits have never been equally distributed in the United States. In McGhee’s words, “Racism has held the pen that has written most of our laws.”

That this history is not taught to Americans is part of the difficulty we face today. Cobb pointed out, for example, that the US paid reparations once before as part of emancipation. The money of course, went to slaveholders to compensate them for the loss of their human property. He also noted that the Homestead Act of 1862, which literally gave federal land to American citizens, largely excluded black Americans from its benefits.

It was in the context of this discussion that McGhee ruefully observed how much of this history was [conveniently] foreign to white America. “We’re a young country; our history is not that hard to know.” American history is at most a few hundred years, in comparison to Asian and European societies that date back thousands of years.

Ultimately, both McGhee and Cobb found reason for optimism. For McGhee, this is the time for dramatic social and economic change: the crisis of the pandemic has loosened white people up; they are more open to new solutions. Her advice is that reformers must seize the moment and move major change. Now is the time!

Cobb encouraged people to take advantage of what he called the most fundamental institution of our democracy: our libraries, which he praised as places where the opportunity exists to cultivate yourself as a person, as a citizen, for free.

“It’s the key to America’s greatness. You can walk into a public library and learn!”, he marveled.

The discussion between these sterling public intellectuals was moderated by Karrie Howard, the Cleveland safety director, whom Cobb singled out at the end for his role in facilitating the discussion.

The program, which concluded with closing remarks from library director Felton Thomas, was validation of Cobb’s praise of libraries, and a virtual demonstration of CPL’s self-appellation as “the People’s University”.

• • •• • •

A note on the participants: Heather McGhee designs and promotes solutions to inequality in America. A reviewer found her new book, The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together, was “predicated on the idea that little will change until white people realize what racism has cost them too.”

McGhee’s 2020 TED talk, “Racism Has a Cost for Everyone” reached 1 million views in just two months online. In the coming year, she plans to launch two original podcasts on the economy and on how to create cross-racial solidarity in challenging times.

Jelani Cobb has been contributing to The New Yorker since 2012. He became a staff writer in 2015. He writes frequently about race, politics, history, and culture and won the 2015 Sidney Hillman Prize for Opinion and Analysis Journalism, for his columns on race, the police, and injustice. He is the author of several books, including The Substance of Hope: Barack Obama and the Paradox of Progress (2015), and The Devil and Dave Chapelle (2007).