Although she lost in the third round to one of her young admirers, Serena Williams went out like the champion she has been, to the delight of millions of her fans watching the match. She elevated her game and played almost like yesteryear to go down swinging.

Serena is considered the best and the greatest female tennis player of all time. Of course, I believe “best” and “greatest” to be two different things, but that is a subject for another day, as I consider her both.

As Serena retires from competitive tennis, she is appropriately lauded far and wide for not only her tennis accomplishments but also how she and Venus changed the game, most prominently to one of power.

Significantly, she is praised for blazing a path for other blacks. As some say, she was widely successful in this “white sport.” While I agree with the perception of tennis as a white sport before Serena and her sister Venus, I must attest to a different reality. Tennis was not a white sport in 20th century America.

Let’s examine why it appears otherwise. The bottom line is that, like many other issues in America, racism is the culprit, which should not be surprising.

In its long history, before the 19th century, tennis was a sport of royalty and the upper classes. However, it began to spread in the United States in the late 19th century at Ivy League colleges. Consequently, African American interest was sparked by blacks from well-to-do families who attended these schools.

Tennis spread among black colleges and upper-middle-class African Americans. Tuskegee started having tournaments as early as 1895. In 1898 a notable black tournament was held in Philadelphia.

By 1910, the Black Press was reporting on the activities of various black clubs: the Monumental Club of Washington, D.C.; the Chautauqua Tennis Club in Philadelphia; the Flushing Tennis Club of New York City; and other clubs in Wilmington, Delaware; New Rochelle, New York; New Haven, Connecticut; Annapolis, Maryland; Atlanta, Georgia; Durham, North Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina; and New Orleans.

In 1916 blacks formed the American Tennis Association (ATA) with several purposes: developing tennis among African Americans, encouraging the formation of clubs and the building of courts, encouraging the formation of local associations, and encouraging and developing junior players.

The following year the ATA began its national tournaments, first held in Baltimore. Both men and women played, with Lucy Diggs winning the women’s championship and becoming the first African American female national champion of any sport. They added a junior division in 1924.

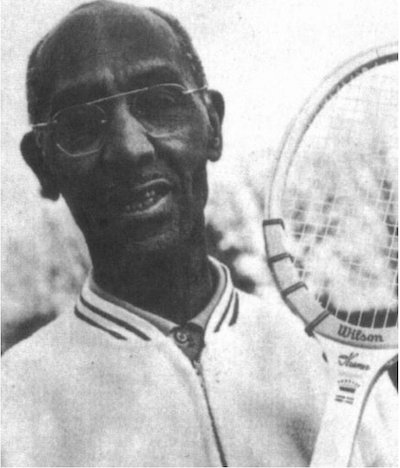

Richard Hudlin was captain of the University of Chicago tennis team in 1927.

Lucy Diggs, the first African American female national champion in any sport. She is best remembered as Lucy Diggs Slowe, the first female Dean of Women at Howard University and a founder of Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority.

In the 1920s, a few blacks were beginning to distinguish themselves as players on predominantly White college tennis teams: Richard Hudlin at the University of Chicago, Douglas Turner at the University of Illinois, Henry Graham at the University of Michigan, and Reginald Weir at CCNY.

Hudlin was captain of his team in 1927, Turner was runner-up in the Big Ten Championships in 1929, and Weir was captain for three years at CCNY.

Richard A. Hudlin, memorialized in this plaque in St. Louis, helped Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe become Wimbledon champions.

Until then, the ATA and the USLTA (the whites-only U. S. Lawn and Tennis Association) were on friendly but segregated terms. In 1921, Dwight Davis, former tennis champion and founder of the Davis Cup international tennis competition, the U.S. Secretary of War, and president of the USLTA, umpired a semi-final match at the ATA Nationals.

By 1929, when black players were competitive, the USLTA's unwritten rule against black participation barred black players, and the ATA had its first confrontation with the USLTA.

Having paid the small entry fee, Reginald Weir and George Norman, Jr. showed up to play at a USLTA junior event in New York City and were turned away when officials learned they were black.

The ATA complained to the NAACP, which complained to the USLTA, and received a letter stating that it was best to “keep the present method of separate associations.” However, the NAACP did not go further, apparently feeling that there were more critical segregation issues to pursue.

• • •• • •

Wornie Reed is Professor Emeritus of Sociology and Africana Studies and Director of the Race and Social Policy Research Center at Virginia Tech University. Previously he developed and directed the Urban Child Research Center in the Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs at Cleveland State University (1991-2001), where he was also Professor of Sociology and Urban Studies (1991-2004). He was Adjunct Professor at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine (2003-4). Professor Reed served a three-year term (1990-92) as President of the National Congress of Black Faculty, and he is past president of the National Association of Black Sociologists (2000-01).

This column first appeared online at What the Data Say and is shared here by permission.