By April Dembosky, KQED

When I’laysia Vital got accepted to Texas Southern University, a historically Black university in Houston, she immediately began daydreaming about the sense of freedom that would come with living on her own, and the sense of belonging she would feel studying in a thriving black community.

Then, a nurse at her high school’s health clinic in Oakland, California, explained the legal landscape of her new four-year home in Texas — where abortion is now fully banned.

Vital watched TikTok videos of protesters harassing women outside clinics in other states. She realized her newfound freedoms would come at the expense of another. That’s when she added one more task to her off-to-college checklist: get a long-acting, reliable form of birth control before leaving California.

“I don’t want to go out there and not know anything, not know where to go, because I’m in a new state. So I’m trying to be as prepared as I can before I leave,” she said.

The change is a huge culture shock for Vital and some of her classmates, who for the past four years at Oakland Technical High School have had access to their own health clinic on campus.

The “TechniClinic” is a bright-purple building across from the football field and bleachers. The school’s bulldog mascot is painted near the door. On-site, students can get free, confidential birth control consults and screenings for sexually transmitted infections and be back at their desks for fourth-period math.

This summer, nurses at the Oakland clinic have formalized the “senior send-off” appointment, during which they counsel students about their legal rights and medical options before they leave for college.

After Roe v. Wade was overturned last year, clinic staffers realized students of color could be disproportionately affected by changes in state abortion laws. Many of them, like Vital, were choosing to go to historically black colleges and universities in Southern states, where bans and limits on the procedure are more common.

“Many students here are just totally floored when I tell them that these laws are different in the states that they’re going to,” said Arin Kramer, a family nurse practitioner at the TechniClinic. Like many adults, “they can’t believe that they can’t get an abortion in this country.”

Kramer has been writing prescriptions for a year’s supply of contraceptive pills or patches, which students can pick up all at once.

Under California law, students can get contraception for free, without having to tell their parents or use a parent’s insurance plan. Students can pick up the prescription at the school clinic, or Kramer can call it in to a pharmacy near the student’s home.

During her own “senior send-off” appointment, Vital told nurse Kramer she was in the market for something even more reliable than pills.

“Because I’m very forgetful. Even if I set an alarm or write it down, it will still slip my mind,” Vital said.

She wanted a long-term contraceptive, like an IUD or a hormonal implant that would last for years and require no upkeep.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Academy of Pediatrics have made these options their top recommendation for adolescents after research from both groups showed they were safe and highly effective at preventing teen pregnancy.

So at Oakland Tech and other school-based health clinics run by nonprofit La Clínica de La Raza, Kramer has trained other nurse practitioners how to insert these devices — so students can get them the same day they ask for them.

After reviewing the options, Vital decided she wanted a contraceptive implant. During their discussion, Kramer used clear, direct terms, even dropping in phrases students use themselves.

“Who are you talking to these days?” Kramer asked Vital, which is teen-speak for: Who are you having sex with?

“Same person,” Vital replied.

“You guys have been off and on, off and on,” Kramer said. “How do you feel going forward?”

“Well, now they’re on because he’s going to Texas, too,” Vital revealed with a smile. “He’s going with me.”

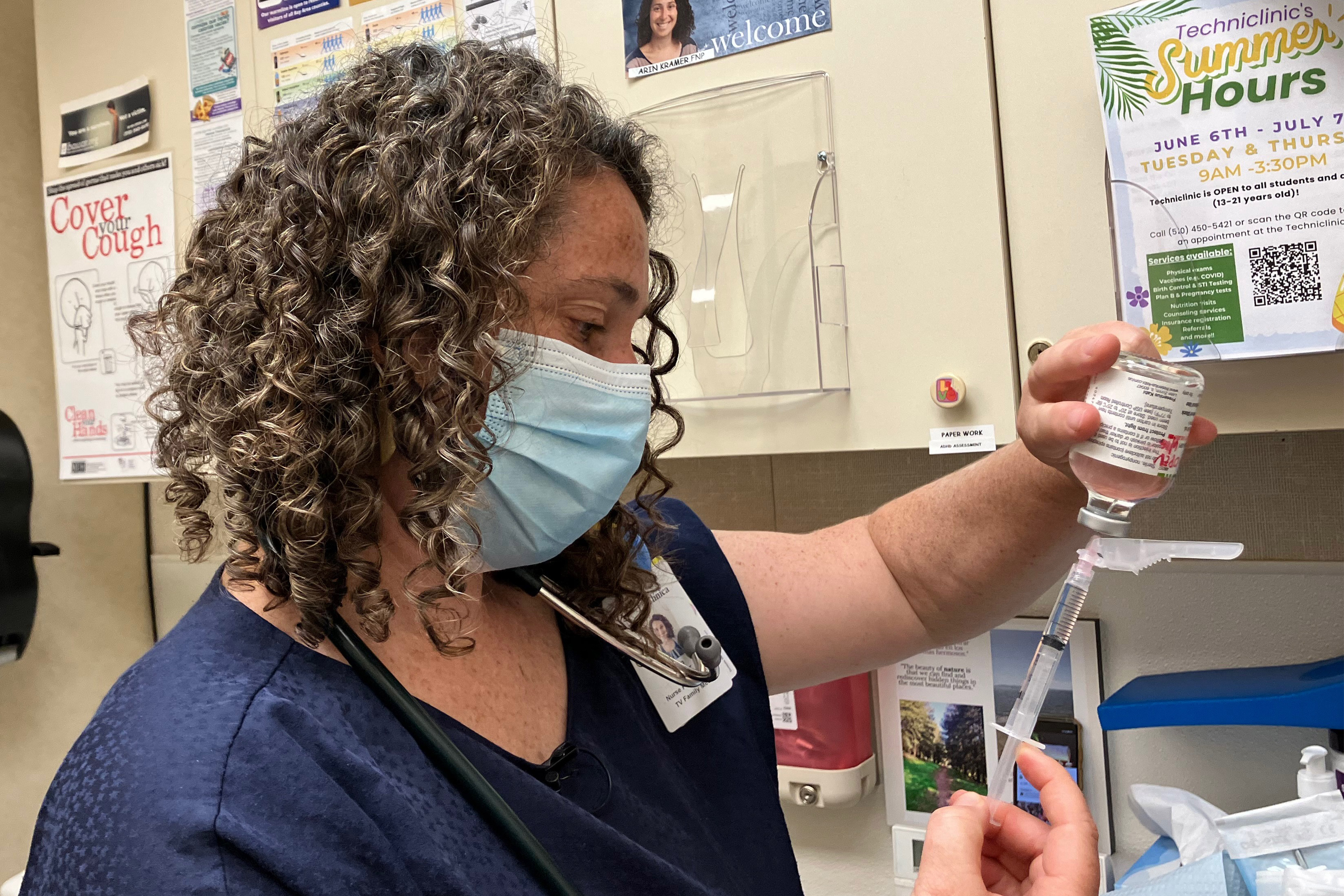

The clinic staff started preparing the exam room, so Vital could get the implant right away. Kramer turned on some calming music on her phone, washed her hands and had Vital lie down and raise her left arm over her head. Physician assistant Andrea Marquez came in to hold Vital’s other hand and offer words of encouragement.

“I’m going to count to three and then you’ll feel a little pinch,” Kramer said, before giving Vital a shot of numbing medication in her tricep area. Then she coached her through a series of deep breaths before inserting the tiny rod under the skin of her upper arm.

The whole procedure took less than 10 minutes, and Vital walked out with a birth control method that will last her up to five years. Now, she said, she can focus on her education and fully experience the new freedoms of college.

“I’m really excited for the growing up part of it,” she said.

Meanwhile, Kramer headed back to her office. She had a list of other patients to check up on, many headed to states that ban abortion. As they pack their books and bed linens for their new dorm rooms, she’s reminding them to also pack a year’s supply of contraception, too.

University-based health centers also are reconsidering their clinical protocols in the wake of the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization Supreme Court ruling that overturned Roe.

In 2020, only 35% of colleges offered on-site IUD insertion and 43% offered contraceptive implant insertion, according to a survey by the American College Health Association.

That group now recommends college clinics do routine pregnancy screenings to identify pregnancies as early as possible, to give students more time to consider their options, and to have legal counsel on call to advise clinicians on allowable practices.

Attorneys might even help advise university health centers about how to have conversations with patients, especially in states like Texas, where local law forbids clinicians from “aiding and abetting” patients who seek abortion care. These new threats — of prosecution or pulled funding — have complicated clinicians’ communication with their collegiate patients.

“So I’m going to be vague with my wording, purposefully,” said Yolanda Nicholson, director of clinical education at the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University health center, and chair for the coalition of Historically Black Colleges and Universities of the American College Health Association.

Nicholson thinks the concept of the senior send-off appointment in the student’s home state is a great one, given that college health centers in Texas and throughout the South have had to adjust their educational approach with students to be more general and “maybe not as specific or targeted as we would have previously done,” to stay aligned with local laws.

Out-of-state students are often shocked to discover they don’t have access to the same services as they do at home, she said.

• • •• • •

This article is from a partnership that includes KQED, NPR, and KFF Health News.