By

When James Burris was sent to quarantine in a solitary confinement cell, the doctor wouldn’t tell him who allegedly exposed him to the coronavirus, citing laws protecting personal medical information.

Burris said he and the four other men sent off to quarantine with him deduced who might have exposed them by comparing notes.

“None of us knew each other,” Burris says. “The only thing we had in common was we all had been in [remote] contact with the Global Tel Link lady.”

Global Tel Link, or GTL, provides digital tablets inmates can use to buy music and rent movies. Burris’ signed up to see the GTL worker because his tablet was broken, but he said he hadn’t even met with her that day because he had been in dialysis. No one in the quarantine group caught COVID-19.

And Burris had something else in common with everyone forced to quarantine: They were all unvaccinated.

The incident underscores a reality of prisons’ attempts to control deadly outbreaks: Both prisoners and prison staff in Ohio are less likely to be vaccinated than other adults in the state.

But the consequences for prisoners and staff who choose not to take the vaccine are very different. States across the country have rolled out incentives and education programs encouraging staff to get the shot, but only a few, like New Mexico, have boosted the staff vaccination rate above the state’s overall rate for adults.

More than 6,600 prisoners tested positive for COVID-19 at some point, including 135 who died, according to an Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections (ODRC) data released this past Monday, Aug. 2. That’s about 15% of the prison population. The death rate was about 28 per 10,000 prisoners.

Although the rate of coronavirus-related deaths for staff members has been lower — about nine deaths per 10,000 staff members — 42% of staff members have had a positive coronavirus test. As of Aug. 2, though cases in prisons have declined dramatically since last summer, there were more staff infected (13) than inmates (four).

With the rise of the highly contagious Delta coronavirus variant, vaccinations are more important than ever. While individual reports of so-called “breakthrough cases” of vaccinated people are not uncommon, they have affected less than 1% of vaccinated people in states that have reported data, according to an analysis by Kaiser Health News. Unvaccinated people accounted for over 90% of COVID-19 infections in those states, and nearly 100% of hospitalizations and deaths.

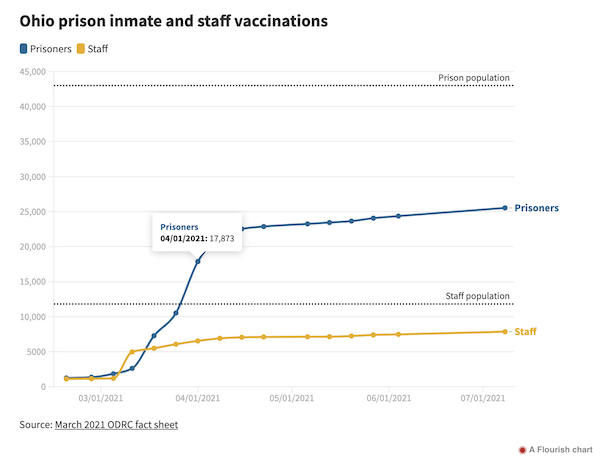

According to the ORDC, 55.3% of Ohio prison staff have opted to take the vaccine, slightly higher than the prisoner vaccination rate of 53.5%. According to the Washington Post, the overall vaccination rate for adults in Ohio is 61.1%.

The Department says that both prisoners and staff are free to decide whether or not they want to be vaccinated, and no one who decides to forgo the vaccine will be punished. But some prisoners view precautionary measures to stop unvaccinated prisoners from spreading the virus as retaliatory.

Like many prisoners, Burris is wary of the shot’s side effects.

“I want to see a little bit more data on it before I even attempt to take it,” he says. “But I felt like I got punished for not taking it, because they put us in solitary confinement quarantine for five days.”

While the department has officially made clear that medical quarantine is not meant to be punishing, prisoners are often placed in the same cells used for disciplinary segregation if there are insufficient medical quarantine facilities. Their access to things like email, telephones, and recreation time while in quarantine can vary. Prisoners like Burris say requests for help in segregation cells are not always answered.

The percentage of prison staff vaccinated varies wildly across states. Other states’ prison systems have tried out a variety of incentives and programs, with uneven success.

Some have tried monetary incentives to get vaccinations. In May, California began offering a vaccine lottery for prison staff, with prizes ranging from $20 gift cards to $1,000 cash. But just 54% of prison staff have taken at least one vaccine dose—well below California’s adult vaccination rate of 73%. Colorado offered $500 gift cards to every prison staff member who got vaccinated, boosting their staff vaccination rate to about 60%. That’s still under Colorado’s statewide adult rate of 69%.

The Ohio Department of Corrections offered just $10 to each prisoner who took both vaccine doses. Some bioethics experts argued that even that amount could be considered coercive, given that prisoners with jobs might make just pennies an hour, and even emails to loved ones cost prisoners money.

“An incentive for something in prison can be something as meager as, ‘we’re going to shave two or three days off your sentence,’” says Wanda Bertram, a communications strategist with the Prison Policy Initiative. “It should tell you a lot about how people are exploited in prison.”

One state that has pushed vaccination rates for prison staff above the general population is New Mexico. As of July 9, 85% of prison staff had been vaccinated through the prison system’s vaccination program, according to spokesman Eric Harrison. That’s higher than the adult vaccination rate for the state overall as of July 7, which was 77%. Harrison noted that the total number of staff vaccinated is almost certainly higher, since it would include staff who got their shots elsewhere.

Vaccinations are especially important in New Mexico’s prisons because they’ve experienced one of the highest per-capita COVID-19 death rates in the country. According to the Marshall Project, there have been 43 deaths for every 10,000 prisoners in New Mexico prisons, or 28 deaths in a prison system of less than 5,000. The raw number of deaths in Ohio’s prisons is much higher at 135, but compared to the size of Ohio’s prison population, the COVID-19 prison death rate is only 28 per 10,000.

Some of the incentives for New Mexico prison staff mirror those in other states, including a statewide vaccination lottery, and shots provided on-site.

But the state also focused on person-to-person education.

Wenceslaus Asonganyi, the director of health services for New Mexico’s prison system, said wardens were getting a regular stream of information about COVID and the vaccine through conference calls every two weeks. The health department would share the latest recommendations with the wardens, Asonganyi said, and then wardens could disseminate that information to workers at their sites.

The department set up COVID “command centers” for both the overall prison system and each individual site. Staff who had questions about the vaccine could visit the site command center and explain their concerns – whether it was about side effects, the vetting behind an FDA “emergency approval,” or different vaccine brands. The site command center would answer if they were able, and if not, they’d turn to the central command center.

“They could link with us immediately through a conference line,” Asonganyi said. “The screen was there. We would actually see them, they would see us, and we could talk about it.”

Usually the site command center would get back to the staff member afterward with an answer, but Asonganyi said the questioners could attend the meetings themselves if they wanted to, and occasionally did.

The central command center was always open for questions during business hours, and when it was closed, a staff member was on call.

Another critical detail, Asonganyi said, was asking staff who didn’t want to get vaccinated to sign a form, instead of just not making an appointment to get the shot.

“I wanted to make sure of that, because just opting out was an opportunity to educate, the opting out itself,” Asonganyi said. “You can’t just opt out of something without knowing what you’re opting out of.… Once you have a formal process to say, ‘Hey, this is really up to you, but this is what we have if you want it, this is how you go about it if you don’t want it,’ the opt out process in itself indirectly is an education process.”

But the system didn’t give up on staff who opted out. With a list of refusals in hand, health staff could reach out to them and ask if they’d changed their minds, or if they had any questions they wanted answered before taking it.

Once someone agreed to take the vaccine, Asonganyi said they worked fast to get the shot in their arm. They set up a system to deliver vaccines to a facility within hours of a request.

“If your system is, ‘Put your name on this list,’...in just that one week or two week time frame, they can change their mind,” he said.

As more and more staff got the vaccine, Asongyi said, convincing others became easier and easier.

ODRC spokesperson JoEllen Smith said via email that ODRC also had a 24-hour central COVID command center at the height of the pandemic, and Ohio, like New Mexico, has vaccines available to staff on-site at prisons. The department set up an email address and phone number where staff could direct questions. Smith also noted that prisons have medical staff trained about the vaccine who could answer questions.

“We attempt to schedule an individual for a vaccine clinic as quickly as possible once they express interest in getting vaccinated,” she said.

But ODRC didn’t ask staff to sign a form if they decided not to get vaccinated.

In Ohio, prison staff are represented by the Ohio Civil Service Employees Association (OCSEA). OCSEA communications director said the union supports COVID-19 vaccine education by posting information from the Ohio Department of Health on social media and union bulletin boards, and shares it through emails and the organization’s magazine.

Ohio prison staff are also able to get the vaccine while on the clock, which OCSEA communications director Sally Meckling says the union supports.

Meckling says the union is proud that the Ohio prison staff vaccination rate is as high as it is.

“Can we do better? Sure,” she said. “There’s always room for improvement.”

• • •• • •

This story is sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative (NEO SoJo), which is composed of 18 Northeast Ohio news outlets including Eye on Ohio, which covers the whole state.

Cid Standifer is a Cleveland-based freelance journalist who specializes in data and investigative reporting, and whose work has appeared in The Plain Dealer, The Washington Post, FreshWater Cleveland, and Stars and Stripes.