I’m blessed to have lived a long life. At 75 I am far older than anyone in my family of origin ever got to be: my mother died just after I turned 21; she had lived a vibrant life, never yielding her spirit to the cancer that afflicted her for twenty years. I cried soundlessly in the hospital when she died, unsurprised but shocked.

My brother Steve, born three years ahead of me, died in his sixties. He was ill in his later years, and his end was forecast before it arrived.

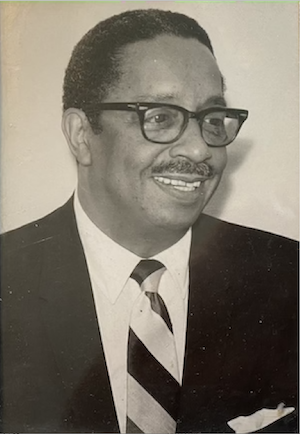

My father’s death at 61 was a surprise. He had just returned from two and a half weeks in Hawaii. He looked tanned and rested when I went to see him on the Sunday a day or so after his return. The Hawaii trip was one of his few bucket list items: the serenity he exuded on our last visit was perhaps a harbinger that he was ready for his heart to stop after breakfast two days later.

My dad was a minister. He was a 37-year-old postal clerk with two degrees, two young sons, and a wife not far removed from radical life-saving surgery (performed by the incomparable Dr. Charles R. Drew) when he was called to his life’s profession.

Setting himself a goal to be ordained by age forty, he undertook a regimen that shaped my early school years. He was on campus at Howard University’s School of Divinity Monday through Friday from 8a-5p, attending classes and studying in the library. He and my mother would come home together around 5:30 —she was a music instructor at Howard — relieve our babysitter/housekeeper, Mrs. Fowler, and we would have dinner as a family. My dad would go to bed at 7p and sleep for less than three hours before heading to his all-night shift at the main Post Office by Union Station on Capitol Hill. He maintained that discipline year-round, including summers, for three years so that he could keep his “by-40” target, something inspired by a quote in Catherine Drinker Bowen’s fictionalized account of the life of Oliver Wendell Holmes.

the post office was known colloquially as “the graveyard of n----- talent”, a reference to the stunted lives of so many black men of brilliance whose paths to fuller, richer lives were blocked by Jim Crow.

Later in life my father told me how the post office was known colloquially as “the graveyard of n----- talent”, a reference to the stunted lives of so many black men of brilliance whose paths to fuller, richer lives were blocked by Jim Crow. The work required mental acuity: in the days before ZIP codes and automation, when first class mail was the internet of the day — clerks were required to know in detail streets, house numbers, cities and states all across the country, in order to “throw schemes”, i.e., to sort the mail so that it would arrive on time at the millions of businesses and homes that were utterly dependent upon the country’s primary communication system.

But the repetitive drudgery was mind-numbing, spirit-crushing, dream-killing [“Hold fast to dreams, for if dreams die, Life is a broken winged bird that cannot fly”]. Its anguish gave rise to the phrase “going postal”.

When I returned to Cleveland in 1972, a major reason was to reconnect with my dad. In my pre-adolescent years here, his energies were consumed with learning his new profession, rebuilding a congregation, and supporting my mother (✅ ✅ ✅). In the parlance of the day, he was a man’s man, which meant you sucked it up, you didn’t show weakness, you didn’t hug other males, not even your sons when they needed it. He administered discipline rarely but memorably, on those occasions heightening my agony by requiring me to fetch the khaki cloth Army belt which he would apply to my skinny butt. [I took possession of that belt after he died, wearing it fondly and ferociously until it disintegrated.]

But those socially reinforced male attitudes were barriers to building a healthy relationship between father and sons, so coming back home as a young man to recalibrate our relationship and reaffirm our love was one of the best decisions of my life. I had spent my entire adolescence away at boarding school and college, trying to navigate indifferent and often structurally and systemically hostile institutions and terrain. I was getting a first-class education, to be sure, but not without immense psychosocial costs. That was not something he recognized or that we could discuss.

Like many black men of his day, my father had a hate-love relationship with the established order of things: he appreciated its order and logic but loathed its color line exclusivity, its gross hypocrisy, and the way it rendered people of color invisible and disposable. He was at core a conservative, believing in eternal values. He was a child of the South, born in Houston, Texas to a once-prominent family whose forbears once had wealth.

In one of his memorable phrases, he told me that he always maintained an “image of the magnificent”. It was something to which he clung in the darkest moments that visit us all; it kept him, he said, from descending to a low point from which there can be no recovery.

my father had a hate-love relationship with the established order of things: he appreciated its order and logic but loathed its color line exclusivity, its gross hypocrisy, and the way it rendered people of color invisible and disposable.

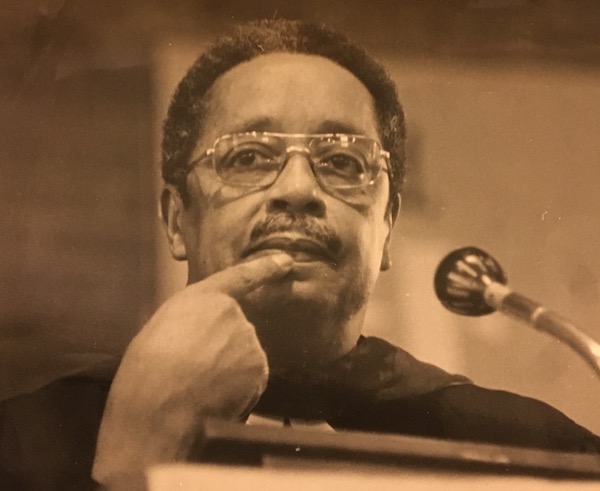

My father’s twenty-one years of ministry were all spent at one church — Mt. Zion Congregational UCC in University Circle. He likely preached about a thousand sermons, which I remember him writing out in his distinctively inscrutable cursive; a natural left-hander, he’d been forced to convert in grade school — a violation of personhood he gratefully spared me. He was conversant with all the great theologians, Tillich, Barth, Kierkegaard, etc., and his sermons and church bulletins were peppered with quotations from G. K. Chesterton, Coleridge, and especially the mystics C. S. Lewis and Howard Thurman. He was adept at translating their deepest cogitations into everyday examples that could assist his middle-class parishioners through the weekly travails of being black in America.

My stepmother donated some of my Dad’s papers and sermon tapes to his alma mater, Howard Divinity School. But I found two or three of his sermon manuscripts and transcribed them with a don's pride and devotion. For comfort, connection, and inspiration, I sometimes read them aloud in my mind’s ear. His was a distinctive sermonic voice. He contracted asthma as an adult and it affected his public speaking. He labored successfully to master breathing techniques so he could speak from the pulpit. But it raised the pitch of his voice a few degrees, as if his lungs had a measure of helium along with his scarce supply of oxygen. Nearly a half century later, I recall his pulpit voice more than his household one.

These reminisces are inspired in large measure by the unexpected blossoming this past week of Juneteenth as a nationally recognized holiday. My father was from his earliest days familiar with Juneteenth as only a black Texan could be. I cannot describe his wry appreciation of the day, but I know he would be amazed at its belated national acceptance. At his core, he would understand not only how far we have come, but how far we still must go.

Happy Juneteenth Dad! Happy Father’s Day. Thank you.

• • •• • •

This post was updated June 20, 2021 at 9:11pm.