The trial of former police officer Derek Chauvin for the murder of George Floyd is underway in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Chauvin, who is white, is charged with second-degree murder, third-degree murder and manslaughter in connection with the death of George Floyd, who was Black, during an arrest last May. For 8 minutes and 46 seconds, Floyd – handcuffed and face down on the pavement – said repeatedly that he could not breathe, while other officers looked on.

A video of Floyd’s agonizing death soon went viral, triggering last summer’s unprecedented wave of mass protests against police violence and racism. Chauvin’s murder trial is expected to last up to four weeks.

These five stories offer expert analysis and key background on police violence, Derek Chauvin’s record and racism in U.S. law enforcement.

1. Police violence is a top cause of death for Black men

Since 2000, U.S. police have killed between 1,000 and 1,200 people per year, according to Fatal Encounters, an up-to-date archive of police killings. The victims are disproportionately likely to be Black, male and young, according to a study by Frank Edwards at the Rutgers School of Criminal Justice, in Newark.

In 2019, Edwards and two co-authors analyzed the Fatal Encounters data to assess how risk of death at the hands of police varies by age, sex and race or ethnicity. They found that while “police are responsible for a very small share of all deaths” in any given year, they “are responsible for a substantial proportion of all deaths of young people.”

Police violence was the sixth-leading cause of death for young men in the United States in 2019, after accidents, suicides, homicides, heart disease and cancer.

That risk is particularly high pronounced for young men of color, especially young Black men.

“About 1 in 1,000 Black men and boys are killed by police” during their lifetime, Edwards wrote.

In contrast, the general U.S. male population is killed by police at a rate of .52 per 1,000 – about half as often.

2. Chauvin has a track record of abuse

Many police officers who kill civilians have a history of violence or misconduct, including Chauvin.

In an article on police violence written after George Floyd’s killing, criminal justice scholar Jill McCorkel noted that Derek Chauvin was “the subject of at least 18 separate misconduct complaints and was involved in two additional shooting incidents.”

During a 2006 roadside stop, Chauvin was among six officers who fired 43 rounds into a truck driven by a man wanted for questioning in a domestic assault. The man, Wayne Reyes, who police said aimed a sawed-off shotgun at them, died. A Minnesota grand jury did not indict any of the officers.

Nationwide fewer than one in 12 complaints of police misconduct result in any kind of disciplinary action, according to McCorkel.

3. Bad police interactions hurt Black families

Even when officers who use excessive force are fired, as Chauvin was after the George Floyd killing, these incidents – occurring so frequently, for so many years – take an emotional toll on Black communities.

In a 2020 Gallup survey, one in four Black men ages 18 to 34 reported they had been treated unfairly by police within the last month.

The racism and inequality researchers Deadric T. Williams and Armon Perry analyzed data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, which surveyed nearly 5,000 families from U.S. cities, and found that negative police interactions have “far-reaching implications for Black families.”

“Fathers who reported experiencing a police stop were more likely to report conflict or lack of cooperation in their relationships with their children’s mother,” they wrote.

Black mothers also report “feelings of uncertainty and agitation” after Black fathers are stopped by police, Williams and Perry found. That can “affect the way that she views the relationship, leading to anger and frustration.”

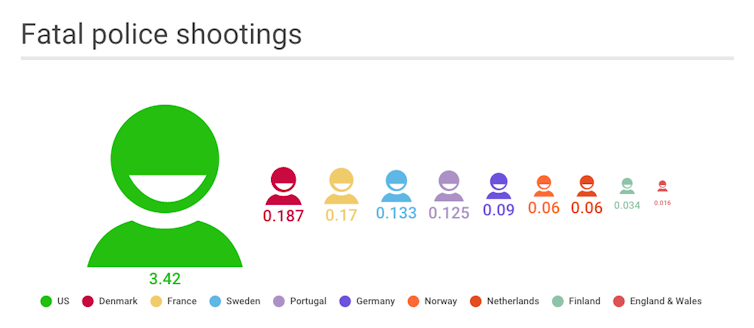

4. This happens far less in Europe

According to a 2014 study on policing in Europe and the U.S. by Rutgers researcher Paul Hirschfield, American police were 18 times more lethal than Danish police and 100 times more lethal than Finnish police.

The top reason for this difference, Hirschfield wrote in an article explaining his findings, is simple: guns.

In most U.S. states, it is “easy for adults to purchase handguns,” Hirschfield wrote, so “American police are primed to expect guns.” That may make them “more prone to misidentifying cellphones and screwdrivers as weapons.”

U.S. law is relatively forgiving of such mistakes. If officers can prove they had a “reasonable belief” that lives were in danger, they may be acquitted for killing unarmed civilians. In contrast, most European countries permit deadly force only when it is “absolutely necessary” to enforce the law.

“The unfounded fear of Darren Wilson – the former Ferguson cop who fatally shot Michael Brown – that Brown was armed would not have likely absolved him in Europe,” writes Hirschfield.

5. American policing has racist roots

Well before modern gun laws, racism ran deep in American policing, as criminal justice researcher Connie Hassett-Walker wrote in June 2020.

In the South, the first organized law enforcement was white slave patrols.

“The first slave patrols arose in South Carolina in the early 1700s,” Hassett-Walker wrote. By century’s end, every slave state had them. Slave patrols could legally enter anyone’s home based on suspicions that they were sheltering people who had escaped bondage.

Northern police forces did not originate in racial terror, but Hassett-Walker writes that they nonetheless inflicted it.

From New York City to Boston, early municipal police “were overwhelmingly white, male and more focused on responding to disorder than crime,” writes Hassett-Walker. “Officers were expected to control ‘dangerous classes’ that included African Americans, immigrants and the poor.”

This history persists today in the negative stereotypes of Black men as dangerous. That makes people like George Floyd more likely to be treated aggressively by police, with potentially lethal results.

• • •• • •

International Editor and Politics Editor at The Conversation.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.